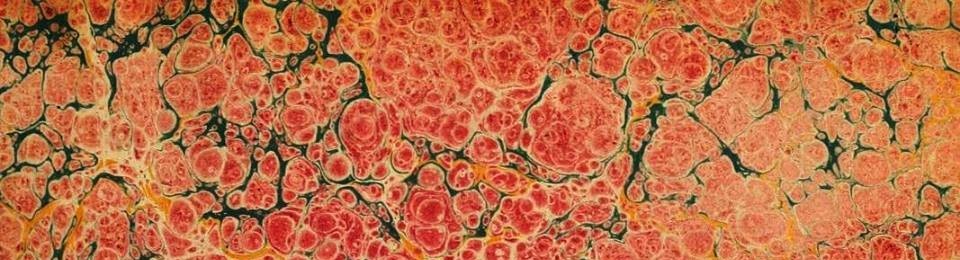

After a map by Isidore of Seville, c. 622 CE

1.

A loaded word, but just a

word. In simpler times and terms, more about which direction

one faced. Facing correctly,

specifically, eastward—or

oriented—the east, or the Orient. Reoriented

from our contemporary perspective: neither right nor

left, our east or west, but upward or northward on the mappae mundi.

Orientem, oriens—the rising sun, the part of

the sky also where the sun rises every morning. Up, as if to imply

over our heads, and slips behind us in the evening time.

How literal and silly cartographers were

back then. Silly as toddlers. As a toddler boy who asks

a simple question: “When my eyes get bigger and bigger, will

I see the whole. World.”

And his mother and father not knowing what he means,

supposing: See it

as it is. As topsy-turvy, turned upon its head, like those old maps

perhaps, which look remarkably as though they’d been drawn

by toddlers’ hands: Their dependence on such thick lines.

2.

Thick black lines, but no longitude or latitude. Though we give them

a lot of latitude for being so simple-minded, such old men,

to think that the world was flat or carried once on a turtle’s back—

our houses being houdahs, our Oriental carpets spun of

magic flax—or a cosmogonic egg,

cracked, poached, over easy or sunny-side up. Made to order. “Order up.”

Silly as Quetzalcoatl or Pangu—moving heaven and earth for you

while walking on eggshells—calculating

Hubble’s constant, constantly counting it out on

fingers and toes and expanding the poles of this

spheroid cosmos, according to one

ancient Chinese legend, like the ends of a breaking

egg separating—as a Big Bang, and as arcane.

3.

Or just plain arcane. Ancient,

archaic. Archaeo-, meaning olden or

from the beginning, like a rising up, oriri, to rise, or *ergh,

similarly, raise or set in motion or stir.

Stirring, too, a beginning: And styrian,*sturjanan, storan—

to scatter or destroy—as much an

end as it is a beginning. As a storm is

also its own refreshment. Or the snake’s consumption of

self is at the same moment a regurgitation of itself:

The Ouroboros, an ancient symbol. Or how the latest found fact of archeology

is simultaneously eschatology:

the last writing being also

the first writing, as in Alpha and Omega. Which is

why the aboriginal—ab origine, from the beginning,

originalis, origo—ever faced

the east, in the first place. In the first

place, which in the last place is why we find ourselves so disoriented. Turning

bigger and bigger telescopes: And so many suns in the sky.

First published in issue 41.1, Fall/Winter 2014, of Black Warrior Review. This poem received a 2014 Pushcart Prize nomination.