Global migratory fish populations have declined by 81% since 1970: but river restoration projects offer hope

Global migratory fish populations have declined by 81% since 1970, according to a major new report released last week. This startling decline has been documented in freshwaters across the world, with particular severity in Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean.

The new Living Planet Index for Migratory Freshwater Fishes states that the downward trend in migratory fish populations represents an annual decline of 3.3%, and is largely the result of habitat degradation and loss coupled with human over-exploitation. The report cites that a key driver of migratory fish declines is the fragmentation of rivers and the blockage of migration routes due to dams, weirs and other barriers.

The report – which monitored 1,864 populations of 284 migratory fish species across the world between 1970 and 2020 – states that habitat loss and degradation – which also includes the conversation of wetlands for agriculture – accounts for half of the threats to migratory species. Overfishing, increasing pollution and the growing impacts of the climate emergency all also contribute to the cocktail of pressures faced by migratory fish.

Populations of migratory salmon, trout, eel and sturgeon – alongside numerous other species – are not only vital to healthy freshwater ecosystems, but they also support the food security and livelihoods of millions of people who live around rivers, lakes and wetlands. This is particularly the case in areas of Africa, Asia and Latin America, where migratory fish support the livelihoods of tens of millions of people through fisheries, global trade and recreational angling.

“The catastrophic decline in migratory fish populations is a deafening wake-up call for the world. We must act now to save these keystone species and their rivers,” said Herman Wanningen, founder of the World Fish Migration Foundation. “Migratory fish are central to the cultures of many Indigenous Peoples, nourish millions of people across the globe, and sustain a vast web of species and ecosystems. We cannot continue to let them slip silently away.”

Despite its startling headline figure, the report contains glimmers of hope. Nearly one-third of the monitored migratory fish species populations have increased since 1970. The authors suggest that this means river restoration projects such as dam removals, habitat restoration and fisheries management can have positive effects on the health of migratory fish populations.

The report – supported by the World Fish Migration Foundation, ZSL, IUCN, The Nature Conservancy (TNC), Wetlands International and WWF – highlights that thousands of river barriers are being removed across Europe and USA. In 2023, 487 barriers were removed across Europe (an increase of 50% on the previous year), whilst in the USA, some of the largest dam removals in history are underway along the Klamath River in California and Oregon.

The challenge is to keep the momentum behind these initiatives growing, to help restore free-flowing rivers that not only benefit migratory fish, but also the wider ecosystem and human communities. The embattled EU Nature Restoration Law – if passed – contains an imperative for European countries to restore 25,000km of free-flowing rivers across Europe, whilst in the USA the the White House’s America the Beautiful Freshwater Challenge Partnership offers the largest freshwater restoration and protection initiative in history. Moreover, major freshwater projects such as MERLIN are providing valuable tools for environmental managers seeking to implement and upscale restoration activities across Europe.

“In the face of declining migratory freshwater fish populations, urgent collective action is imperative,” said Michele Thieme, Deputy Director, Freshwater at WWF-US. “Prioritising river protection, restoration, and connectivity is key to safeguarding these species, which provide food and livelihoods for millions of people around the world. Let’s unite in this crucial endeavour, guided by science and shared commitment, to ensure abundance for generations to come.”

Read the 2024 Living Planet Index for Migratory Freshwater Fishes

///

A guest post by Monika Böhm, Freshwater Conservation Coordinator, Global Center for Species Survival, Indianapolis Zoo

///

Freshwater ecosystems play a vital role in sustaining biodiversity and supporting human livelihoods. They are also under immense pressure: for example, the WWF Living Planet Report shows that vertebrate populations are declining more rapidly in freshwater ecosystems than in terrestrial and marine systems!

Critically, major international biodiversity agreements – agreements aimed at stemming the loss of species, populations and ecosystems – are also focusing on halting freshwater declines. We need to be able to monitor progress towards the targets set by these biodiversity agreements to evaluate if they are successful in achieving their aims. However, effective monitoring of freshwater ecosystems still lags behind monitoring of terrestrial systems, and is often not carried out in a coordinated manner across regions and countries.

This is where the Global Freshwater Macroinvertebrate Sampling Protocols Task Force (GLOSAM) comes in. This group – which operates under the umbrella of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission (SSC) – has recently published a first and important review of the current state of freshwater biodiversity monitoring programs, focusing on the use of benthic macroinvertebrates as indicators.

What are benthic macroinvertebrates?

Benthic macroinvertebrates are aquatic invertebrates (animals without a backbone) that are large enough to see without a microscope: think worms, molluscs (snails and mussels), crustaceans, and the larvae of aquatic insects such as stoneflies, mayflies, caddisflies or dragonflies. ‘Benthic’ refers to the association of these animals with the bottom of a water body.

Why monitor benthic macroinvertebrates?

By monitoring freshwater macroinvertebrates such as insects, crustaceans, molluscs, and worms, scientists and conservationists can also monitor freshwater health. The presence and abundance of these species provide key information on the status of freshwater ecosystems in relation to human-made threats. Insights from such monitoring allows us to make smarter decisions in freshwater management.

Macroinvertebrates are great for monitoring because they have limited movement or are in some cases even sessile, and are therefore great indicators of the localised conditions they are “stuck in”. They cover a range of species and higher taxa that not only reflect a range of positions in the food web, but also different pollution tolerances. Through their positions in the food web, they serve as a major food source for many fish.

On a more pragmatic level, macroinvertebrates can be abundant in most streams, including those that may be too small to support many fish. They are relatively easy to sample, requiring few people and inexpensive gear, and they are relatively easy to identify to more coarse taxonomic levels, so any experienced general biologist should be able to use these animals to detect or recognise degraded conditions.

Benthic macroinvertebrate sampling protocols – a study

Protocols using benthic macroinvertebrates exist for both bioassessment and biodiversity monitoring. While bioassessment and biodiversity monitoring sound similar, they are not the same. Bioassessments aim to evaluate the status and/or condition of a waterbody by sampling and analysing a representative subset of macroinvertebrates.

Biodiversity monitoring tries to document the full variety of biota in ecosystems, from a system’s genetic diversity and species diversity to its ecological and functional diversity. Ultimately, biodiversity monitoring aims to assess trends in the ecosystem’s diversity. So there is overlap between bioassessment and biodiversity monitoring, including in the design and techniques used, but they have traditionally been carried out separately.

To find out about the uptake of freshwater benthic macroinvertebrate protocols by practitioners across the globe, the team conducted a comprehensive survey from the end of 2022 to mid–2023. Overall, 110 individuals from 67 countries participated in the survey.

From the survey data, the GLOSAM team, led by Drs. John Simaika (IHE Delft) and Andreas Bruder (SUSPI) and comprised of a core group of 15 researchers, government officials and NGO representatives from around the globe, identified a notable gap in biodiversity monitoring efforts at the national and sub-national levels: while bioassessment programs were more prevalent, there was a lack of systematic biodiversity monitoring across lakes, rivers, and artificial waterbodies.

Ultimately, GLOSAM’s work is to achieve the harmonisation and standardisation of bioassessment and biodiversity monitoring protocols, to ensure that our freshwater sampling efforts achieve the best value for all, including for our freshwaters. From the survey data, the team identified several distinct gaps and challenges that we must address to ensure that biodiversity monitoring and bioassessment protocols are well aligned.

For example, while protocols for biodiversity monitoring require us to sample across different water bodies, habitats, and seasons to get as full an inventory of biodiversity as possible, protocols for bioassessments stipulate that similar water bodies, habitats and seasons are sampled for the most meaningful results.

Other examples include the inherently different taxonomic resolutions at which the two processes of bioassessment and biodiversity monitoring operate. There are also some challenges that apply equally to both biodiversity monitoring and bioassessment, for example that data may often not be made publicly available or may not be in an accessible form and hence not available for analyses.

Probably most notably, the lack of harmonisation of sampling protocols emerged as a significant barrier to collaboration and comparability of data across regions. Given that the ultimate aim is to ensure efficient and effective sampling is carried out that produces the best possible data to track progress towards international biodiversity targets, overcoming this challenge is of the utmost importance.

Following this initial survey effort of sampling protocols, GLOSAM’s next step is to address this issue: to improve available datasets that can give us insights into species distributions and population sizes over space and time, and to give us a better understanding of the impacts that human activities have on freshwater ecosystems and their macroinvertebrate inhabitants.

Dr Simaika says: “Efforts to monitor and assess the health of freshwater ecosystems are critical for conservation and sustainable management. By addressing the identified gaps and challenges and promoting global harmonization, we can enhance the effectiveness of biodiversity monitoring programs and ensure the long-term resilience of freshwater ecosystems. Collaborative initiatives such as GLOSAM provide a pathway towards achieving these goals and safeguarding the invaluable biodiversity found within freshwater habitats.”

///

To learn more about GLOSAM, its goals, activities, members and partners, visit the Task Force’s website.

It is well documented that Europe’s ecosystems are in urgent need of protection and restoration. However, as the debates over the EU Nature Restoration Law have shown, getting ambitious nature recovery projects off the ground is not always straightforward.

A common problem is that whilst there may be public and political support for environmental projects, there is often a critical lack of financing to make them happen in practice. The EU MERLIN project has recently released new tools to help environmentalists access funding sources to help make their projects a reality.

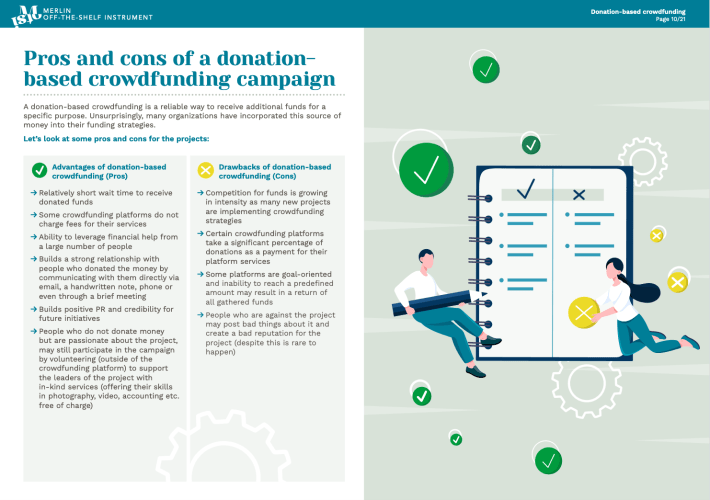

Working with the consultancy firm CONNECTOLOGY researchers from MERLIN have published two ‘Off-the-Shelf Instruments’ which demonstrate the potential of donation-based crowdfunding and corporate donations to help finance environmental projects.

The idea behind these Instruments is that the urgency of the biodiversity crisis and climate emergency, coupled with the slow pace of political processes, requires us to look more broadly at new forms of funding to help bring degraded ecosystems back to life. The authors suggest that, “these instruments not only facilitate public funding but also acknowledge the indispensable role of private finance in propelling impactful initiatives forward.”

The two Off-the-Shelf Instruments released this week are the first of a series exploring new forms of environmental funding. Each Instrument includes an overview of the pros and cons of the funding source, alongside best practice guides, case studies, timelines and suggested Key Performance indicators (KPIs) for implementing them.

You can keep up with the release of new Off-the-Shelf Instruments on the MERLIN website.

Donation-based crowdfunding

Crowdfunding has emerged has emerged as a key mode of gaining financial support for charitable and environmental projects in recent years. Supported by the rapid growth in mobile technologies, crowdfunding involves backers (or donors) providing financial support to help make projects happen.

Donation-based crowdfunding means that this financial support is offered by backers without the expectation of anything in return. Money is instead offered towards supporting projects – such as river restoration – which a backer sees as worthwhile.

The MERLIN researchers suggest that such donation-based crowdfunding can not only help attract financial support for environmental projects, but its ability to ‘travel’ online through social media means there is the potential for wide new audiences to be engaged in the issues it seeks to address.

The researchers outline the need to create a strong and compelling story over why crowdfunding is needed, and how the funds are going to be spent. They highlight how this approach requires skilful communications across blog posts, social media and FAQs to keep backers updated with project progress, milestones and outcomes.

The team highlight a case study of donation-based crowdfunding on Rothley Weir in Leicestershire, UK. A campaign by The Rivers Trust was launched on the WWF’s Crowdfunding website in July 2021 seeking support to help remove a redundant dam which was harming the health of the river’s ecosystem. Within three months, the campaign had received over €12,000 in donations, and by September 2021 the dam had been removed.

You can read the full guide to donation-based crowdfunding for environmental projects here.

Corporate donations

Companies, foundations, and other private organisations often make financial donations to support social causes, environmental projects and community schemes. These donations are often framed as a means of a company voluntarily managing or mitigating its impacts on society and the environment.

These donations are not always financial; instead ‘in-kind’ donations of machinery, expertise, materials or volunteer workforces can be useful to environmental organisations in need of support. Whether financial or in-kind, such donations are valuable as they don’t require organisations to provide a financial return to their donors.

The MERLIN researchers identify three main forms of corporate philanthropy: corporate giving programmes; company-sponsored foundations; and ad-hoc requests from organisations. Matching gifts is a common form of corporate giving programmes, where an organisation will financially multiply donations made from their employees.

Corporate donations can potentially offer environmental organisations free funding and assistance for their projects, and raise awareness of their causes. However, it is important to note that corporations are profit-making entities, and the reputation, activities and corporate interests of donor organisations, and their reasons for donating, should be closely scrutinised.

The team highlight a range of successful examples of corporate donations supporting environmental projects across Europe. For example, a €10 million donation from Volkswagen AG in 2018 facilitated repairs to storm damage on the Ebro Delta in Spain, supported UNESCO Biosphere Reserves in Spain, Poland and Germany, and helped restore the Barnbruch woodland in Germany.

You can read the full guide to corporate donations for environmental projects here.

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

We’re delighted to share the latest episode of the MERLIN podcast with you.

Join us on the banks of the Danube River in Austria to hear how ambitious restoration projects are helping free the river from human alterations. We meet Robert Tögel and Alice Kaufmann from viadonau and Silke Drexler from BOKU beside the river to hear about how restoring its banks and side-arms is helping benefit both people and nature. As the trio explain, this work is a process of ‘learning from the river’ to help create space for natural processes to return, whilst at the same time making sure that navigation routes along the river are not impeded.

Back in Vienna, we hear from Helmut Habersack in the recently-opened BOKU River Lab to find out how centuries of alterations of the river interact with emerging pressures from the climate emergency and plastic pollution. We speak to Piret Nõukas from the Research Executive Agency at the European Commission to get a wider picture of how freshwater restoration work in MERLIN fits in with wider EU environmental policies like the Green Deal. And finally, we hear from Eva Hernández, co-ordinator of the WWF’s Living European Rivers initiative to discuss the pressing need to restore rivers across the continent, and how the proposed EU Nature Restoration Law – if passed – could help achieve this goal.

You can also listen and subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Podcasts. Stay tuned for the next episode soon!

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

After months of debate and revisions the EU Nature Restoration Law was approved by the European Parliament in late February. The law represents an ambitious step towards restoring Europe’s depleted ecosystems, requiring EU countries to restore at least 20% of their land and sea by 2030, and all ecosystems in need of restoration by 2050.

The EU Nature Restoration Law is a significant response to the fact that over 80% of European habitats are in poor condition and in need of restoration. Moreover, it foregrounds the vital roles that nature plays in supporting our lives, whether through food security, flood protection or water supplies. On a continent increasingly stressed by the effects of the climate emergency and economic crisis, it offers a hopeful vision of fostering more sustainable and resilient societies and economies in the future.

Despite significant lobbying from opponents, the law was approved in the European Parliament with 329 votes in favour, 275 against, and 24 abstentions. It will now move to the European Council for adoption ahead of its ratification into law. European countries will then need to submit – and regularly update – national restoration plans to demonstrate how they will restore their lands, seas and freshwaters over the coming decades.

A key element of the Nature Restoration Law is its commitment to restoring 25,000km of free-flowing rivers across Europe by 2030. Free-flowing means that a river can flow without major obstacles like dams, hydropower plants and weirs. Such obstacles can significantly alter the flow and course of a river, which can shift how it responds in times of flood and drought. Moreover, they can restrict the movement of fish and insects along a river’s course, which can particularly impact the health of migratory fish populations like salmon and sturgeon.

Free-flowing rivers are not only good for nature, they also represent a break from decades-old thinking on river management, which sought to channel, store and control water flows in order to support human activities. All across Europe, this new thinking has resulted in widespread dam removal, designations of ‘Wild River’ National Parks, and protests against hydropower construction in recent years.

The adoption of the Nature Restoration Law adds further momentum to this growing movement. This work is timely and much-needed: research suggests that there are over 1.2 million barriers fragmenting European rivers, with more than 156,000 of these being obsolete. Such obstacles are linked to significant biodiversity losses, including a 93% decline in freshwater migratory fish populations across Europe.

A team of European researchers have examined how the restoration of free-flowing rivers across Europe will be supported by the Nature Restoration Law. Their study – supported by BioAgora and published in WIRES Water – suggests that whilst there is significant potential for positive work, there remain a number of obstacles to overcome for the law to be a success for Europe’s rivers.

“It is important to underline that the Nature Restoration Law is an absolutely needed step in the right direction, also clearly confirmed from a scientific point of view,” said Dr. Twan Stoffers, lead author of the study, from IGB Berlin. “But river ecosystems are complex networks and their connectivity plays an important role. Hence, clear definitions of the central terms in the law are crucial for enabling efficient implementation.”

The research team – led by researchers from Leibniz Institute of Freshwater Ecology and Inland Fisheries (IGB) in Berlin and the University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences (BOKU) in Vienna – identified seven key challenges for the implementation of the Nature Restoration Law in restoring free-flowing European rivers.

Challenge 1: Defining free-flowing rivers

Successful environmental laws are usually underpinned by clear legal definitions. This means that to restore free-flowing rivers, we need to better define what they are, and what they do for people and nature. The authors suggest the definition of: “free-flowing rivers as fluvial systems in which ecosystem functions and services are unaffected by any human-induced change in fluvial connectivity.”

Challenge 2: Prioritising interconnections across landscapes

A river isn’t an isolated system: its water flows can ebb out onto floodplains, down into groundwater and out into the atmosphere. These interconnections with the wider environment change with time, as seasonal rhythms of flood and drought pulse along its catchment. The authors highlight that these dynamic interconnections need to be taken into account in river restoration. They suggest that defining minimum river section lengths to be restored is a good way of fostering these landscape-scale networks.

Challenge 3: Thinking big about ecosystems

Just as the water in a river isn’t confined to its course, neither are the ecosystems that it supports. So-called ‘meta-ecosystem’ thinking describes the ways that complex webs of life – fish, insects, mammals, birds, plants and more – are interconnected across land and water in a river catchment. The authors state that supporting large-scale ecological systems in Europe’s rivers requires significant collaboration between people and institutions across national and regional borders.

Challenge 4: Making sure free-flowing rivers benefit biodiversity

Two of the key strategies for restoring free-flowing rivers through the Nature Restoration Law are removing barriers such as dams and weirs, and restoring natural flow dynamics across floodplains that have been cut-off by artificial structures. The authors highlight that whilst these strategies are valuable, they need to be carried out in areas which can significantly benefit the health and diversity of river ecosystems. They suggest a need for a prioritisation process which highlights where restoration activities can best boost biodiversity across the continent’s rivers.

“Restoring an additional 25,000 km of free-flowing rivers by 2030 will not suffice to halt the decline of freshwater biodiversity, let alone reverse it,” said Prof. Sonja Jähnig, co-senior author from IGB Berlin. “Due to the relatively small number of rivers to be restored, the implementation should focus on areas where restoration efforts will result in the most substantial improvements to ecological conditions, freshwater resources, and ecosystem services. In fact, it makes little sense to prioritise restoring degraded systems while still degrading near-natural or pristine systems at the same time.”

Challenge 5: Bringing people into the process

Rivers across Europe have been misused and neglected for decades because they have been narrowly viewed as a resource to power extractive industries, intensive agriculture and urban development. This has led to many rivers being trapped in concrete channels, their flows stilled and shrunken, and the webs of life they support hidden from view. The authors state that this needs to change. Bringing European rivers back to life is not only about restoring biodiversity, but also putting people at the heart of the change. This means both communicating the needs for healthy, free-flowing river systems to wide audiences, but also – crucially – listening to people who live and work in river catchments and considering their needs.

Challenge 6: Resolving conflicts with other European policies

The ways in which rivers have been widely neglected by human activities is also reflected in European policy. The authors argue that conservation and restoration efforts are not given the same priority in European policy as competing interests such as agricultural production (e.g. through the Common Agricultural Policy) or hydropower generation (e.g. through the Renewable Energy Directive). They state that there is a pressing need for the Nature Restoration Law to showcase how economic interests can be balanced (and made more sustainable) with environmental goals

“A law can only be as good as its practical implementation,” said Prof. Sonja Jähnig. “We already see that with the Water Framework Directive, aiming at reaching the good ecological status or potential of water bodies. Despite turning into force over 20 years ago, the implementation deficit is still huge. But to give it a positive spin: the Nature Restoration Law could be a booster and role model for the Water Framework Directive activities, if its implementation is done right.”

Challenge 7: Mapping new approaches to monitor and manage river systems

As we’ve seen, the Nature Restoration Law is hugely ambitious, but its goals of restoring free-flowing rivers across Europe face a number of challenges. The authors identify the potential of new technologies such as environmental DNA (or eDNA) to help support how rivers are governed and managed through better ecological monitoring. In short, if new environmental thinking on large-scale landscape and ecosystem interconnections is to be embraced, there is the need for innovative new ways of monitoring and managing their dynamics across river systems.

The new study provides an invaluable road-map to guide European environmental policy makers and managers in the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law over the coming months and years.

///

River restorationists from across Europe met last week in Vienna to discuss the progress of the European Green Deal MERLIN project. Over the course of four days, attendees – which included scientists, water managers, finance experts and investors – collaborated in discussions around the seventeen sites across Europe where MERLIN is working to kick-start river restoration with ambitious new approaches.

The discussions – held in the impressive surroundings of the BOKU River Lab – were well timed given the positive outcome of the latest European Parliament vote on the adoption of the Nature Restoration Law. MERLIN’s work in restoring rivers, streams, peatlands and wetlands across the continent through innovative nature based solutions will provide a vital platform to support restoration across Europe in the coming years and decades.

On the final day, attendees were taken on a trip along the banks of the Danube River, close to the Austrian border with Slovakia. Here, project partners from viadonau are working to reconnect formerly-dammed side arms of the Danube, and to renaturalise its banks. Their work aims to reintroduce more natural habitat and to reconnect the river with its floodplain. Attendees learnt about how this work can be balanced with the navigation needs of ships travelling along the Danube’s course.

“We’ve now been through almost two-thirds of this project, and it’s simply amazing to witness the positive energy of all our collaborators — MERLIN seems to increasingly hit the nerve,” said project co-ordinator Sebastian Birk. “We all want to contribute eagerly to changing the usual business. And with the positive vote on the Nature Restoration Law that coincided with the beginning of the meeting, the tone was somehow set for this memorable event.”

“I’m immensely impressed by the motivation of the partners and their willingness to learn – scientists learn about catchment restoration, catchment managers about finances, finance experts about science,” added project leader Daniel Hering. “MERLIN is one of the most satisfying projects I have ever been involved in.”

Watch this space for a new episode of the MERLIN podcast recorded at the meeting, which will offer an in-depth look at the restoration projects on the Danube, and the importance of MERLIN’s work to the Nature Restoration Law and European restoration more broadly.

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

MERLIN Innovation Awards celebrates state-of-the-art approaches to freshwater restoration at 2024 ceremony

The winners of the annual MERLIN Innovation Awards – which highlight cutting-edge solutions for freshwater restoration – were announced earlier this month. Entries from organisations across the world were assessed by an expert panel, and shortlists for the two categories – Service of the Year and Product of the Year – were compiled. Two winners were announced at a busy online ceremony on February 8th.

The winners of the Product of the Year are Planet Srl for their Mangrove Technology Platform, a modular planting system which facilitates the planting and growth of trees in arid regions without adversely depleting freshwater sources.

This is achieved in two key ways. First, a desalinisation system harnesses sunlight to convert saltwater into freshwater, which allows water from mangrove ecosystems to be used for irrigation. Second, an efficient irrigation system helps water the deep roots of the planted trees without wasting water.

Mangroves are one of the few forest ecosystems that can grow in hot and arid climates. Found across the Gulf of California in Mexico, the Middle East, Western Australia, subtropical Africa and Western South America, mangroves are vital ecosystems which support rich biodiversity and fisheries, and can lock up significant quantities of carbon from the atmosphere.

The Mangrove Technology Platform is designed to help support the restoration of these valuable forests in areas where environmental pressures from heat and drought are common. Supported by an innovative digital monitoring system, the Mangrove Technology Platform allows trees to be planted in marginal areas, which in turn reduces competition with farmers for fertile soil and freshwater supplies. Overall, this provides a valuable nature-based solution to help boost carbon sequestration in arid landscapes.

“In the face of escalating land degradation, aggravated by increasing aridity, traditional tree planting confronts challenges of poor tree survival rates,” said Giulia Berni from Planet Srl. “The Mangrove Technology Platform emerges as a transformative solution, specifically designed to address these bottlenecks. By leveraging abundant saltwater and regenerating dryland, the MTP sets a new standard in agroforestry, offering a low-entry barrier solution that directly tackles the challenges faced by tree planting providers and organisations involved in carbon farming.

“With a sharp focus on resolving water scarcity, soil degradation, and low tree survival rates, the MTP aligns precisely with the critical needs of its customers, providing a sustainable pathway to scale up tree planting activities in challenging environments towards carbon neutrality,” Berni explained.

Planet Srl is an Italian enterprise which develops innovative products which help solve contemporary environmental issues. Its Mangrove Technology Platform is inherently passive – meaning that it works through processes of evaporation and condensation triggered by the sun’s rays. Moreover, unlike traditional approaches, its desalinisation process does not discharge brine as a waste product: instead producing edible salt as a byproduct.

“Winning the MIA Product of the Year award is an incredible honor and validation of the hard work and dedication that went into developing the Mangrove Technology Platform,” said Giulia Berni. “This recognition not only boosts our team’s morale but also increases the visibility and credibility of our innovative solution on a broader scale. The MERLIN project gave us the opportunity to showcase the MTP and interact with a diverse and dynamic audience, including environment restoration project managers, members of the freshwater ecosystem community and innovative companies across Europe.

“This exposure opens up new possibilities for partnerships and collaborations, allowing us to further refine and scale our technology,” Berni continued. “By being part of the MERLIN Marketplace and engaging with various stakeholders, we can accelerate the adoption of the MTP and contribute to the systemic, transformative change needed in our society and economy. Ultimately, winning this award helps us spread and realise our vision of promoting sustainable tree planting in arid regions while addressing water scarcity, to keep working towards carbon neutrality on a larger scale: no green without blue.”

The winners of the Service of the Year are SEADS for their Blue Barriers, which are used to collect and remove plastic waste from rivers. These barriers are designed to be suspended on the river’s surface, and SEADS state that they collect close to 100% of plastic pollution in a waterway.

Between 70 and 80% of the total plastic pollution in the world’s oceans enters via rivers: totalling an estimated 10 million tonnes each year. As a result, projections suggest that by 2050 there may be more plastic in the oceans than fish, with significant negative consequences for the health of marine ecosystems. Further, it is increasingly recognised that microplastics are contaminating the food we eat and the air we breathe.

SEADS’ Blue Barriers are designed to tackle this plastic crisis. They are intended to be unobtrusive to boat traffic and to have negligible effects on wildlife living in rivers. Crucially, the Blue Barriers are economically self-sustaining, as SEADS provide sorting and transport services for the plastic waste which is collected and then transformed into recycled plastics, building materials and energy production. SEADS suggest that this means that the costs of Blue Barrier installation can be repaid in as little as three years.

“Our approach involves the development of floating barriers designed to halt plastic waste before it can enter the ocean,” said Fabio Dalmonte from SEADS. “This proactive measure is crucial because once plastic reaches the ocean, it becomes extremely challenging to collect. In fact, only 1% of ocean plastic remains on the surface, with the majority sinking to the ocean floor where it’s virtually impossible to retrieve. By intervening at the river level, where collection is efficient and targeted, we can make a significant impact.

“Our Blue Barriers are engineered to withstand seasonal flooding and can capture waste up to one metre deep in the water,” Dalmonte continued. “They are designed with exceptional flooding events in mind, ensuring safety and effectiveness. This is particularly important because much of the waste is transported during seasonal rains, not only on the river’s surface but also within the first 50cm below the water’s surface.”

Early testing of the Blue Barriers system has been carried out at the University of Florence and along the Tibor and Lamone rivers in Italy, and long-term installations are now active on the Aniene and Sarno rivers. SEADS now intend for the system to be installed more widely in countries across the world.

“Receiving this award is a tremendous honour and a testament to the dedication and teamwork of the entire SEADS team,” said Fabio Dalmonte. “We’ve put in a lot of hard work, and it’s incredibly rewarding to see our efforts recognized.

“The MIA network presents invaluable opportunities for us,” Dalmonte continued. “Establishing connections through this network is crucial for our project’s success. Whether it’s forging relationships with public administrations, attracting potential sponsors, reaching out to clients, or exploring partnerships, the MIA network can significantly amplify our reach and impact. Undoubtedly, increased visibility through this network will also be instrumental in our journey forward.”

The MERLIN Innovation Awards celebrates new and widely-applicable solutions for restoring freshwater ecosystems. The awards – organised by project partner Connectology – recognise the need for restoration projects to better engage with economic markets to support transformative ecological improvements.

You can find out about the ten shortlisted projects, and the expert jury who selected them.

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.

The relationship between agriculture and the environment is a hot topic in Europe right now. In recent months farmers across the continent have been protesting to highlight a system they see as increasingly unprofitable and burdened by EU rules aimed at making the bloc climate-neutral by 2050. Farmers have organised motorway and city blockades in tractors across Greece, Germany, Portugal, Poland and France, and last week pelted the European Parliament in Brussels with eggs.

In many ways, the farmers are feeling a perfect storm of economic repercussions of the Ukraine war and COVID pandemic, coupled with the ambitious new climate directives passed down by the EU. Costs of energy, fertiliser and transport have risen across the continent following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine two years ago. However, governments across Europe have sought to manage the effects of spiralling interest rates and the cost of living crisis by stemming rising food prices.

Whilst costs are up and profits are increasingly squeezed, European farmers are also feeling the pressure of a changing climate. 2023 was the year that the extremes of the climate emergency were starkly evident across the continent, as record-breaking droughts, wildfires and irrigation restrictions became commonplace across Southern Europe.

Amidst the challenges of producing food in a changing climate, farmers have to work within the rules set by the EU, which attempt to shift our agricultural system towards a more biodiversity-friendly and climate-neutral state. The European farming sector accounts for around 11% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions, and as such will require significant reorganisation to achieve the European Green Deal goal of making the bloc climate-neutral by 2050.

Crucially, whilst the negative effects of intensive agriculture on European biodiversity are well documented, farmers argue that the targets in the EU’s Farm to Fork strategy and Nature Restoration Law to reduce their environmental impacts are overly punitive in the current economic climate. These targets include cutting fertiliser use by 20% and halving pesticide use by 2030, alongside allocating more land to non-agricultural use and doubling organic production.

In the wake of this wave of farmers’ protests the European Commission this week announced it was cancelling plans to half pesticide use in the EU by 2030. And last week, the bloc also announced delays to regulations on set-aside land intended to boost soil health and biodiversity in farmland across the continent.

This leaves European environmentalists in a tricky situation. Clearly, European farmers are increasingly squeezed economically. However, it is increasingly agreed that there is an urgent need for transformative actions to help preserve and restore European ecosystems. A key element of this work is to make agriculture more sustainable, both economically and environmentally.

As such, there is a pressing need to understand how different forms of agricultural practices affect European ecosystems, and whether the most harmful approaches can be transformed in ways that can support both nature and farmers’ livelihoods.

A new study explores how the impacts of different agricultural approaches across Europe affect the ecological health of rivers and streams across the continent. A research team led by Dr. Christian Schürings from UDE in Germany analysed data on agricultural land use across 27 European countries. Writing in Water Research, the researchers then linked this analysis to data on the ecological status of flowing waters across the continent, from small streams to huge rivers like the Ruhr and Rhine.

They found that the health of river and stream ecosystems in Europe is strongly influenced by the type of agriculture that is practiced in the landscapes which they flow through.

“Intensive farming has the greatest impact,” says Dr. Schürings. “This includes irrigated agriculture, as practiced in Southern Europe, for example in Spain, Portugal and Italy, and the intensive use of pesticides and fertilisers on land in Western Europe. This is particularly common in France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Germany and the U.K.”

In many ways, this is not a surprising result. Aquatic scientists have long highlighted the negative impacts of intensive agriculture on our freshwaters, particularly due to pesticide and fertilisers polluting waterways, floodplains being lost to farmland, rivers straightened and abstracted for irrigation. The new study offers is a valuable map of where such agricultural pressure on freshwaters are highest across Europe – particularly clustered in Southern and Western Europe.

On the other hand, the study shows that less-intensive and organic forms of farming have little-to-no negative impacts on the rivers and streams which they border. Small-scale agriculture, which involves less chemical inputs and often occurs over a mosaic of habitats including hedgerows and fallow land, is shown by the authors to be a more river-friendly alternative to existing intensive practices.

“Our results underline that the transition to more sustainable forms of agriculture, such as organic farming, is beneficial for rivers,” says Dr. Schürings. However, the key question remains, how can this transition remain economically viable for farmers?

Decades of agricultural management under the Common Agricultural Policy have encouraged farmers to pursue economies of scale, where profits are boosted by bigger and more efficient farm holdings. Amidst the turmoil of farmers’ protests, how can the need to protect and restore freshwater life be upheld in decisions over how to manage European agriculture?

For co-author Dr. Sebastian Birk, the answer lies in the benefits that healthy, functioning ecosystems can provide to humans. As explored in the MERLIN project, such nature-based solutions can offer a system in which farmers can be economically rewarded for shifting their practices to benefit the environment.

In river catchments, this can include the restoration of floodplains to naturally-buffer flood waters, or the creation of wildflower meadows to boost pollinating insect populations. Such approaches could offer farmers incentives to reduce their environmental impacts, whilst benefiting economically from the healthy functioning of the ecosystems on which they rely.

For Dr. Birk, this means that, “water protection and agriculture can go hand in hand. The EU should support this through a restructuring of agricultural subsidies, so that the environmental services provided by agriculture are more strongly rewarded.”

///

MERLIN Podcast EP.6 – Water, climate and farming: making space for stream restoration in Portugal

In this episode of the MERLIN Podcast we explore the issues around stream restoration in the Sorraia catchment in Central Portugal.

Restoration of the Sorraia river needs to be able to navigate the needs of intensive agriculture in a landscape increasingly affected by the climate crisis. Walking along the banks of the river, we meet a range of freshwater scientists, activists, farmers and policy experts to understand the big issues in the Sorraia catchment, and the ways in which restoration is increasingly making space for this river in the landscape.

We also hear about how work on the Sorraia relates to wider debates over farming, freshwater restoration and the proposed EU Nature Restoration Law.

You can also listen and subscribe to the podcast on Spotify, Amazon, and Apple Podcasts. Stay tuned for the next episode soon!

///

This article is supported by the MERLIN project.