Exhibition dates: 9th March – 2nd June, 2024

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

100 Calotypes by D. O. Hill, R.S.A., and R. Adamson album front cover

1845

60.9 x 43.1cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Album of 109 salted paper prints from calotype negatives by Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847). Assembled and sold to marine painter Clarkson Stanfield (English, 1793-1867) in 1845. Six prints tipped in over other prints; these are likely the prints sent by Hill to Stanfield in January 1846.

The Clarkson Stanfield Album: an album of 109 salted paper prints from calotype negatives compiled by Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847), the photographs created by the painter (Hill) and photographer (Adamson) during a four year partnership that only ended with the untimely death of Robert Adamson at the age of 26 years. What a truly beautiful album full of the most meditative portrait photographs that you could ever lay your eyes on.

Reminiscent of the characteristics of Mannerism in the Renaissance, the figures and hands dance in convoluted poses of asymmetrical elegance. Witness the sway of body and sinuousness of hands in James Drummond, Artist, Edinburgh (1843-1845, below) with the oppositional direction of the hands, one pointing up and the other down. Or the directional composition of My Sister (1843-1845, below) where the sitter looks left in profile, the hand clutching a book (probably the bible) points in the other direction, whilst the other hand touches the earth. The use of chiaroscuro is magnificent. Other masterpieces of the photographic art are replete with the sensitivity of both artists: the double profile portrait of Jas & Thomas Duncan; A Study (1843-1844, below), both staring intently out of the pictorial frame, one brother clutching the other’s shoulder and arm along with his spectacles. Wonderfully intense and atmospheric.

“As artistic director, Hill composed each picture, placing his sitters as they might appear in the finished painting. Adamson operated the camera and carried out the chemical manipulations. Hill and Adamson were a perfect team. Hill, twenty years older than Adamson, was trained as a painter and had important connections in artistic and social circles in Edinburgh; he easily attracted a distinguished clientele to the team’s portrait studio at Adamson’s home, Rock House… Both men had a profound understanding of the way the world would translate into monochrome pictures.”1

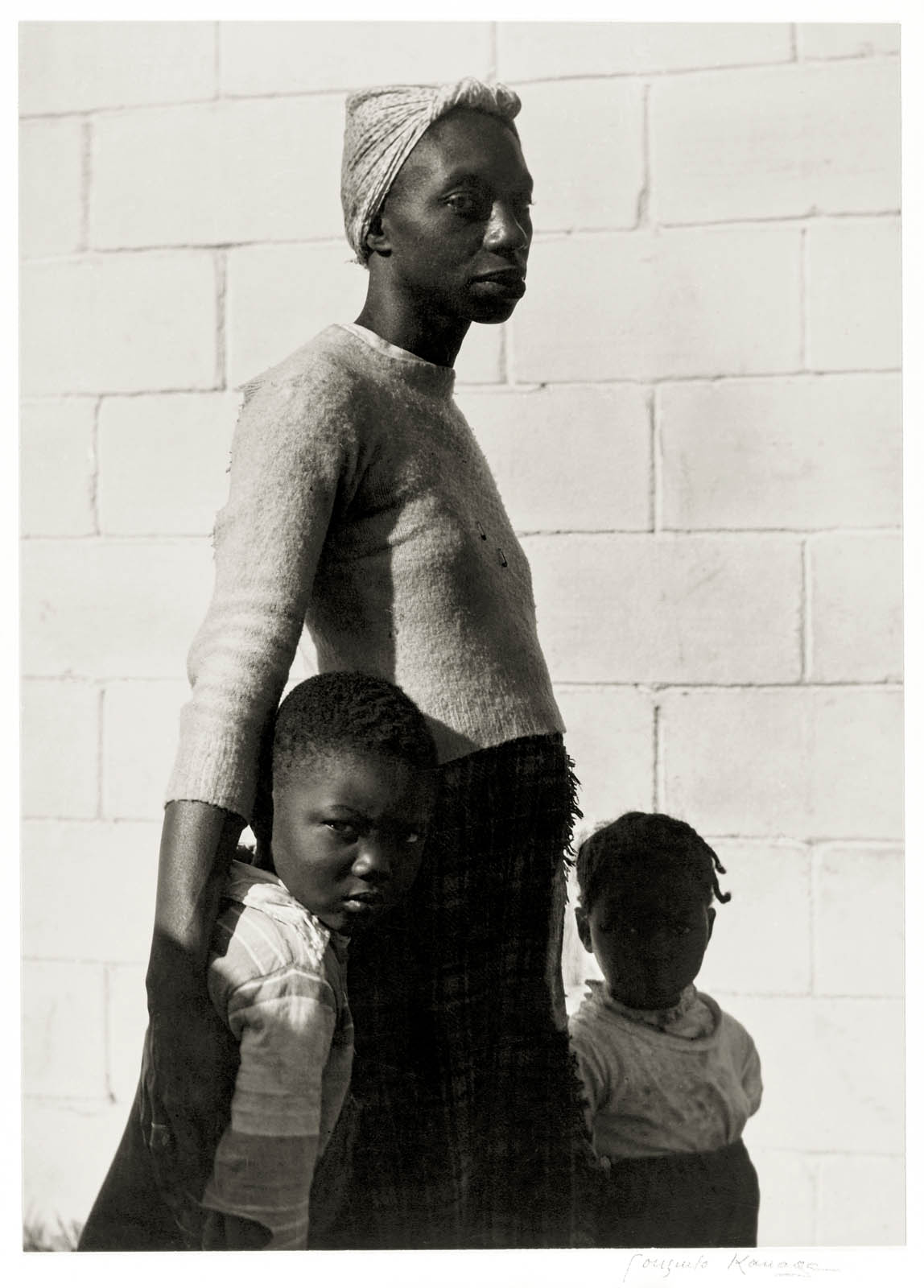

Hill & Adamson also had a profound understanding of how the spirit of a person could be captured by the camera. The Newhaven portraits of fishermen and fishwives – “part of a social-documentary project, the first in photography, that the team carried out in Newhaven and other small but vital fishing towns near Edinburgh”2 – are still to this day some of the most engaging of the early portrait photographs in the history of photography. They capture the character of these people who after all this time still speak to us of their tough life and work through romantic photographs such as the barefooted boy “King Fisher” with his willow basket on a low table or Jeanie Wilson, Newhaven (1843-1845, below) dressed in traditional striped apron and woollen petticoat.

“Hill and Adamson presented Newhaven as a model community bound by tradition, honest labor, and mutual support – qualities emphasised by the careful posing of figures and by the graphic strength and gritty effect of the medium itself.”2

But as Fraser Linklater observes in his article, “‘They put a creel aroond my back and bid me call my haddies’: The Newhaven Fishwives, Preserving Lost Community History and Cultural Transmission Through Generations,” these were staged photographs: “the fact that the Newhaven fisherwomen were wearing ‘gala-dress’ in these pictures reveals it was not an accurate portrayal of them going about their daily work, but instead a picture of a romanticised and imagined community based on some form of semi-truth… Understanding these small details greatly assists us in, once again, grounding their experiences in reality, avoiding polishing their stories to an image that dissuades further thinking and investigation.”

“Nowadays, the village sits subsumed within it’s larger neighbours, Edinburgh and Leith, both in physicality but also, in the last half century culturally…”3

So all we have left of this culture, much like the romanticised photographs of the “Vanishing Race” of the North American Indian by Edward S. Curtis, or the gritty, realist photographs of Skinningrove by Cris Killip eighty or so years later, are these remembrances of times past.

During their brief but prolific partnership Hill & Adamson captured the spirit of these people living in an Industrial Age, photographs that don’t necessarily represent reality but are a performative view of their life and existence at that time (they were performing for the camera, dressed up in their best, posed for effect). But this romanticisation of the people in Hill & Amadson’s Newhaven portraits doesn’t make them any less valuable as representations of that time and place, for that is now all we have.

Indeed, their photographs “show us today some things that we may no longer have access to and give us a window into eyes of real human beings”4 as they go about their daily lives, however staged the photographs might be. Even as evolution would ultimately destroy that way of life forever, so the spirit of past times echoes down to us through these photographs, ripples in a pond caused by a pebble dropped into water.

Dr Marcus Bunyan

1/ Daniel, Malcolm. “David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (1821-1848).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hlad/hd_hlad.htm (October 2004)

2/ Anonymous. “Newhaven Fishwives,” on The Metropolitan Museum of Art website Nd [Online] Cited 31/05/2024

3/ Fraser Linklater. “‘They put a creel aroond my back and bid me call my haddies’: The Newhaven Fishwives, Preserving Lost Community History and Cultural Transmission Through Generations,” on the Scotland Sounds wdebste, 3 September 2020 [Online] Cited 31/05/2024

4/ Shannon Keller O’Loughlin (Choctaw) of the Association on American Indian Affairs (AAIA) in an email to the author, 1 June 2018

Many thankx to the Harry Ransom Center for allowing me to publish the photographs in the posting. Please click on the photographs for a larger version of the image. The photographs in the posting are in the order they appear in the album. You can view all 109 photographs on the Harry Ransom Center website.

PLEASE NOTE: the photographs in the posting are not necessarily the photographs in the exhibition. I have selected my favourite photographs from the online resources of the complete album which are free to download and are in the public domain.

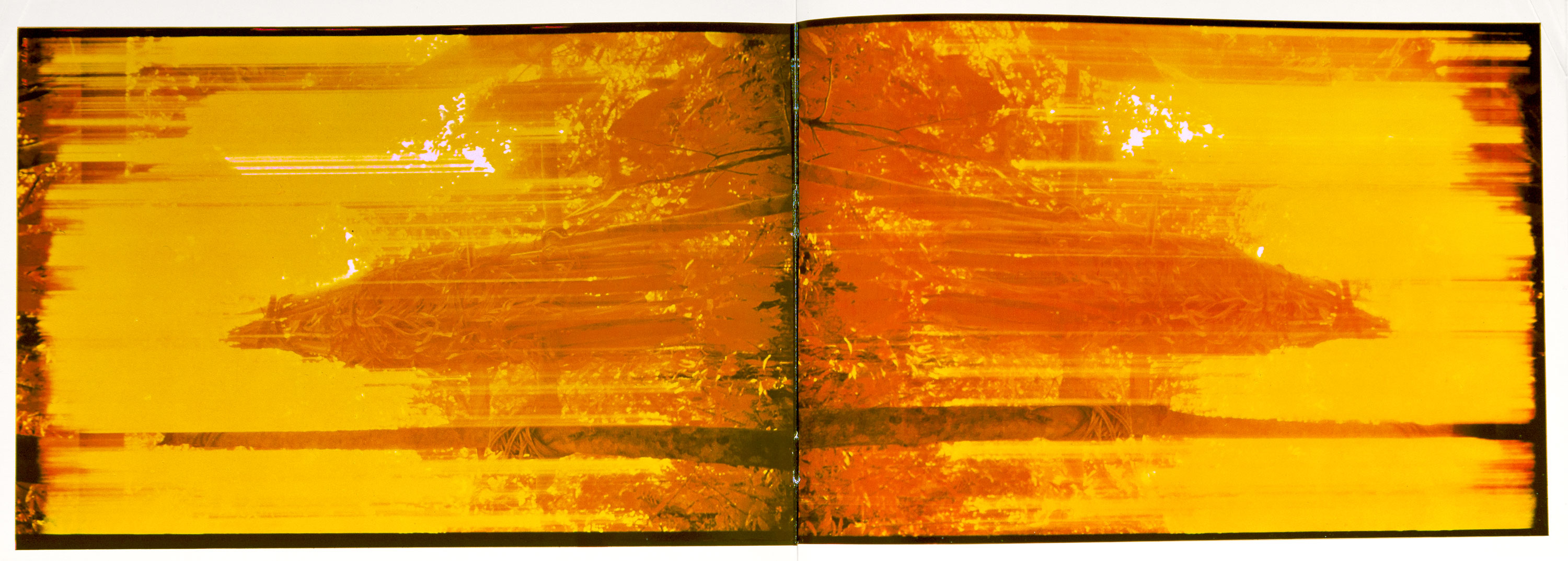

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

100 Calotypes by D. O. Hill, R.S.A., and R. Adamson album endpaper

1845

60.9 x 43.1cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

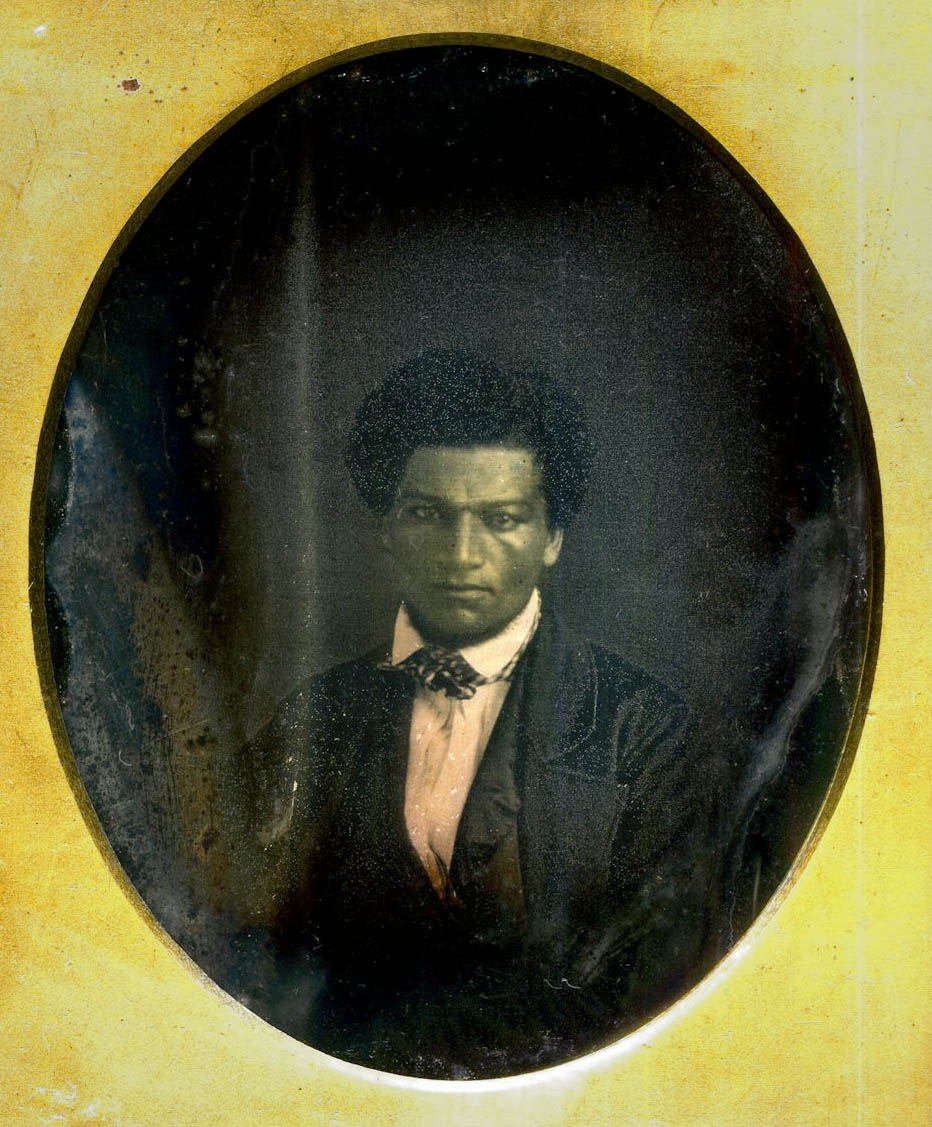

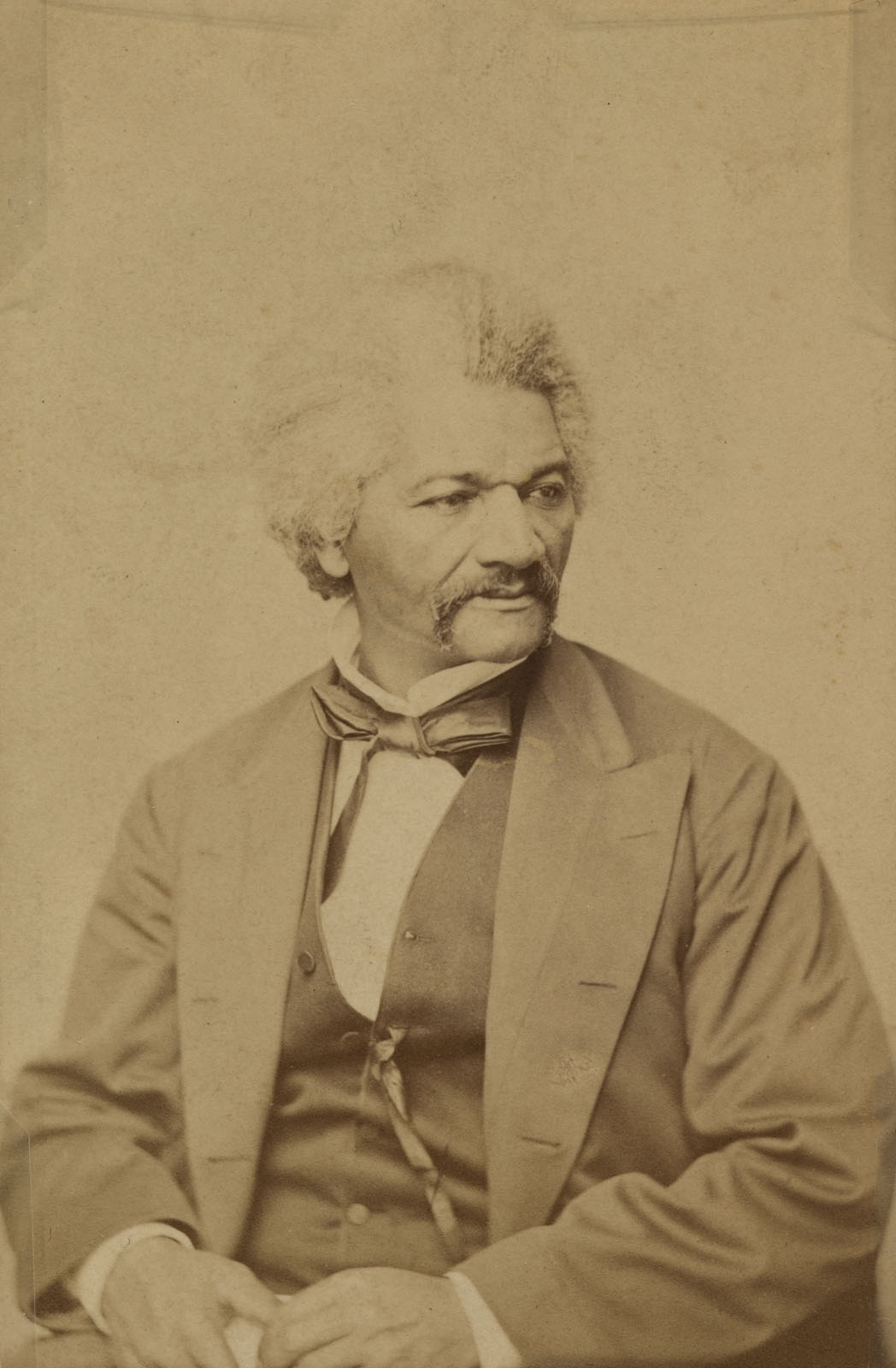

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Robert Adamson

1843-1844

Salted paper print

9 x 6.4cm (arched top)

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Robert Adamson (1821-1848), photography pioneer. Page inscribed with Clarkson Stanfield’s initials and date

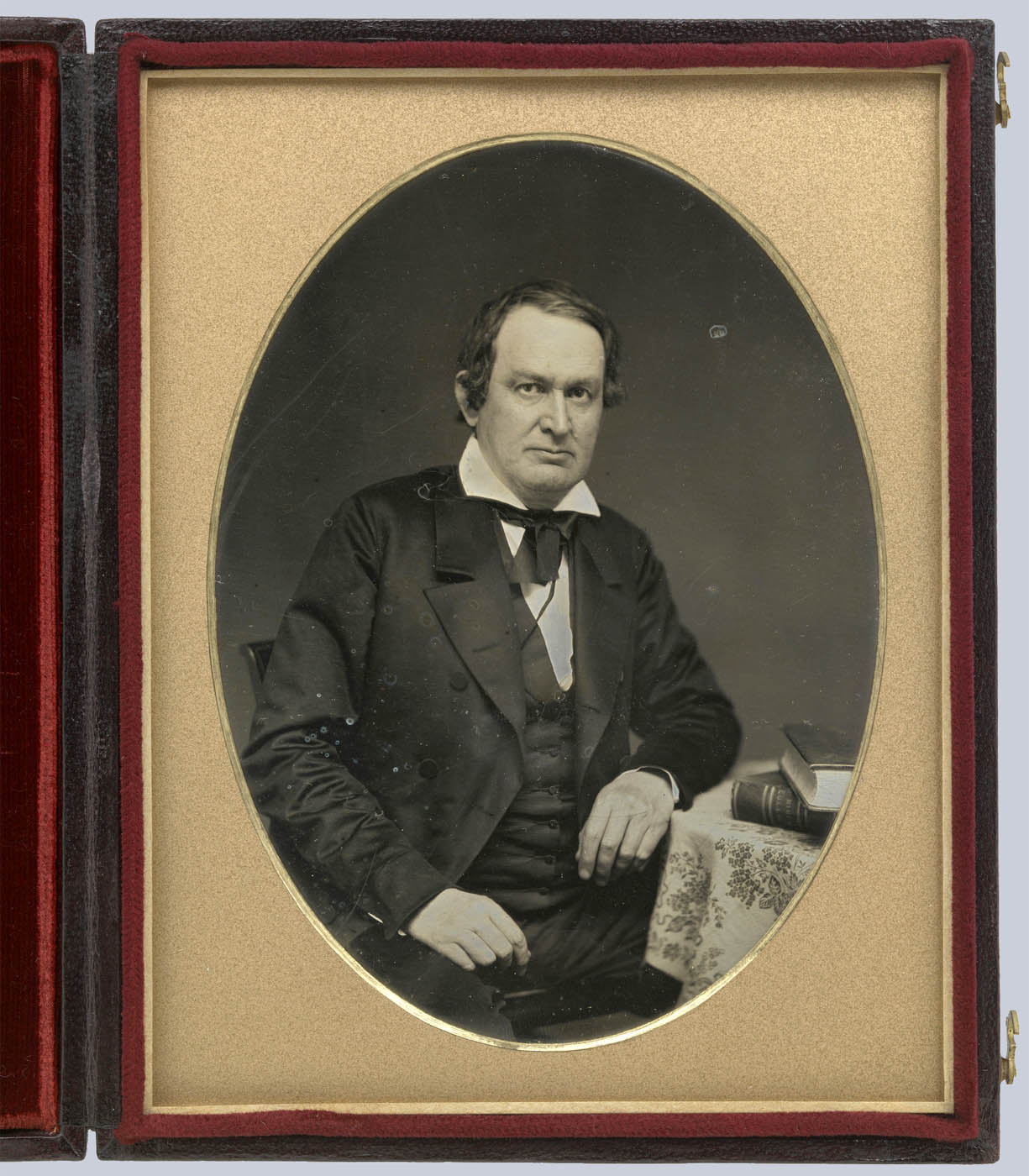

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

D. O. Hill, R.S.A.

1843

Salted paper print

19.8 x 14.1cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

David Octavius Hill (1802-1870), artist and photography pioneer. Mounted on title page with lettering by Hill

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Rev Jas Julius Wood, Late of Greyfriars, Edinb.

1843

Salted paper print

20 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Rev. Dr James Julius Wood (1800-1877), Free Church minister. Secondary inscription by Helmut Gernsheim

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Rev Jas Julius Wood, Late of Greyfriars, Edinb. (detail)

1843

Salted paper print

20 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

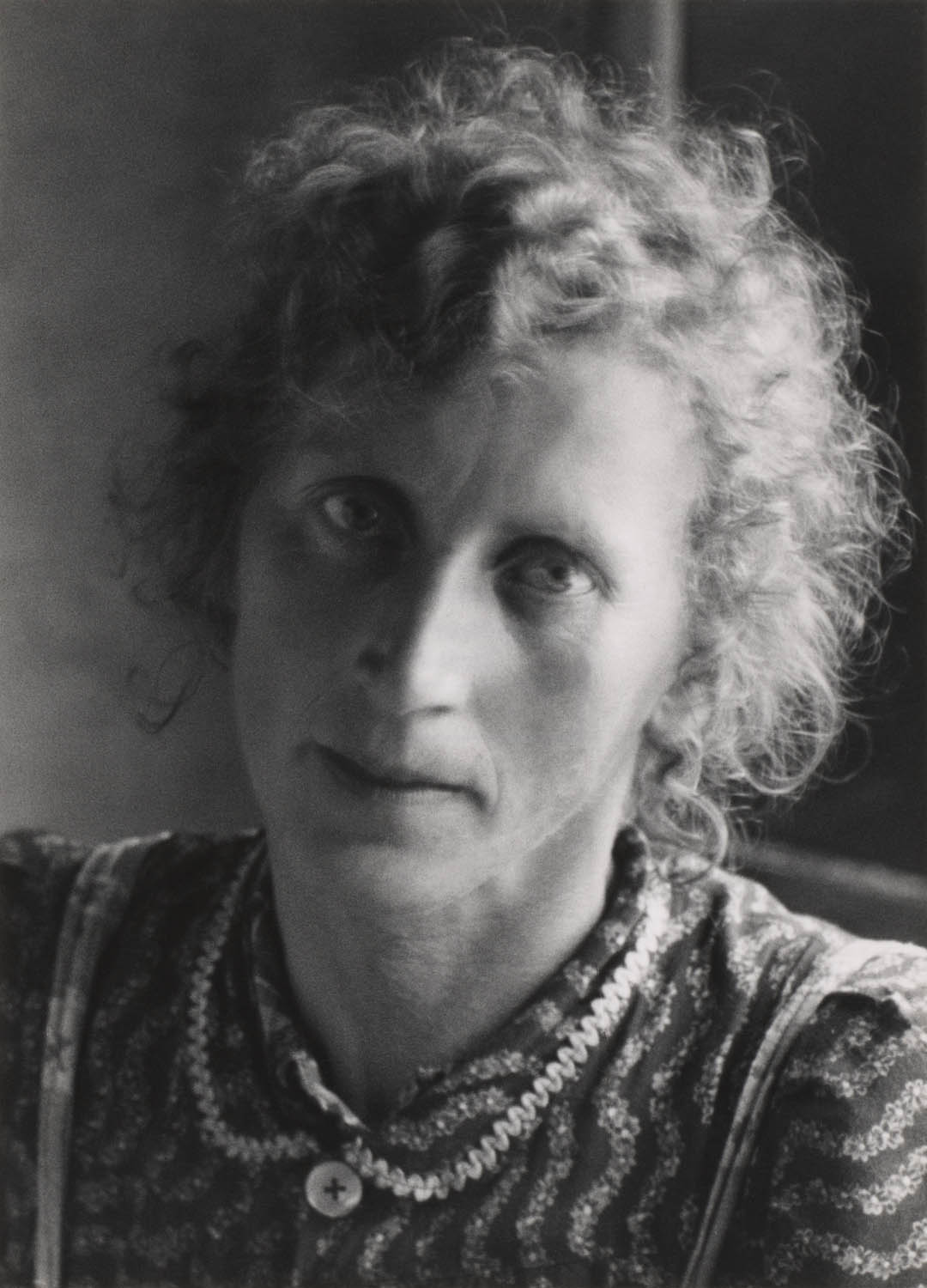

Miss Rigby

1843-1845

20.3 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Jane Rigby (1806-1896), sister of Elizabeth, Lady Eastlake (née Rigby)

Don’t miss this unprecedented exhibition of the Clarkson Stanfield Album, a superb volume of early photographs by the celebrated Scottish partnership of Hill & Adamson. Launching their collaboration in Edinburgh in 1843, the established painter David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and the young photographer Robert Adamson (1821-1848) combined their aesthetic sensitivity and technical brilliance to produce an unparalleled body of portraits, architectural and landscapes scenes, and pioneering social documents. Their work endures today as one of the earliest sustained explorations of photography as an artform.

In the fall of 1845 Hill & Adamson prepared an album of their finest work, arranging over 100 salted paper prints from their calotype negatives into a folio bound in rich purple leather with intricate gold tooling, and sold it to the prominent English marine painter Clarkson Frederick Stanfield (1793-1867). Now known as the Clarkson Stanfield Album, it is one of only a few such unique albums assembled in the years before Adamson’s death at age 26.

More than 175 years later the album is undergoing structural repair, providing the first opportunity since 1845 to view several sections at once before conservators return them to the original binding. The exhibition includes 39 salted paper prints from the Clarkson Stanfield Album, as well as examples of Adamson’s earliest photographic trials and two of Hill’s painted landscapes. The exhibition is drawn entirely from the Gernsheim Collection, acquired by the Ransom Center in 1963.

Text from the Harry Ransom Center website

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

James Drummond, Artist, Edinburgh

1843-1845

Salted paper print

20 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

James Drummond (1816-1877), history painter, Curator of the National Gallery of Scotland

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

James Drummond, Artist, Edinburgh (detail)

1843-1845

Salted paper print

20 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

My Sister

1843-1845

21.1 x 14.8cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Mary Watson (née Hill), sister of David Octavius Hill. Secondary inscription by Helmut Gernsheim

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

My Sister (detail)

1843-1845

21.1 x 14.8cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Miss Parker

1844-1845

20 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Possibly Jane Sophia Barker (née Harden) (1807-1876)

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Jas & Thomas Duncan; A Study

1843-1844

11.5 x 14.9cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

James Duncan; Thomas Duncan (1807-1845), artist

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Jas & Thomas Duncan; A Study (detail)

1843-1844

11.5 x 14.9cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

“100 Calotypes by D. O. Hill, R.S.A., and R. Adamson,” commonly known as the Clarkson Stanfield Album, is a unique album assembled and sold to English marine painter Clarkson Stanfield (1793-1867) before October 1, 1845. The folio, bound in purple leather with gold tooling, contains a total of 109 salted paper prints from calotype negatives made between 1843 and 1845. As originally assembled, the album begins with portraits of Adamson and Hill, followed by 100 plates and a final photograph, perhaps serving as a visual epilogue or postscript. The major themes of Hill & Adamson’s work are represented: the 100 principal plates comprise, in this order, 44 portraits, including two presbytery groups; 10 scenes in Greyfriars churchyard; 2 scenes at Leith; 31 photographs of fisherfolk, mainly at Newhaven; 1 photograph at St. Andrews; and 11 views of monuments and architecture in and around Edinburgh. Titles of most plates are inscribed in Hill’s hand. Six additional salted paper prints were added later; these are likely the prints sent by Hill to Stanfield in January 1846, added to the album by Stanfield. Of these six prints, five are Newhaven photographs and one is a portrait. This is one of Hill & Adamson’s earliest albums, and one of only a few assembled in Adamson’s lifetime. It provides a view into their partnership at its midpoint, and into which images they understood to be some of their strongest thus far. As an object, the album offers a sense of what the partners may have envisioned for other deluxe volumes they announced but never realised. The album is part of the Gernsheim Collection, purchased in 1963.

While the title suggests there are 100 images contained in the album, there are actually 109 salted paper prints, most of which are accompanied by inscriptions provided by either Hill or Adamson. The images are of prominent men and women of the day, friends and acquaintances of Hill and Adamson, and scenes of Edinburgh, Newhaven and St. Andrews, and Scottish architecture and art. The nine additional images can explained in several ways. First, six images cover/originally covered other images. It appears that Hill and Adamson did not like their original choice of several images and later mounted different images over the originals. In most cases, the covered image is very similar to another image in the album (compare 964:0048:0044, a covered image, with 964:0048:0045). Second, the first two images in the book appear on the half-title and title page, and therefore may not have been counted as part of the “100” referred to on the title page. And, a third explanation may be that the cover for the album was printed before Hill and Adamson’s selection of images to be included.

Text from the Harry Ransom Center website

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Edinburgh Castle from the Greyfriars

1843-1845

11.6 x 15.9cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Greyfriars Churchyard; a group of monuments including the Chalmers and Jackson Monuments, with Edinburgh Castle in the background

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Edinburgh Castle from the Greyfriars (detail)

1843-1845

11.6 x 15.9cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

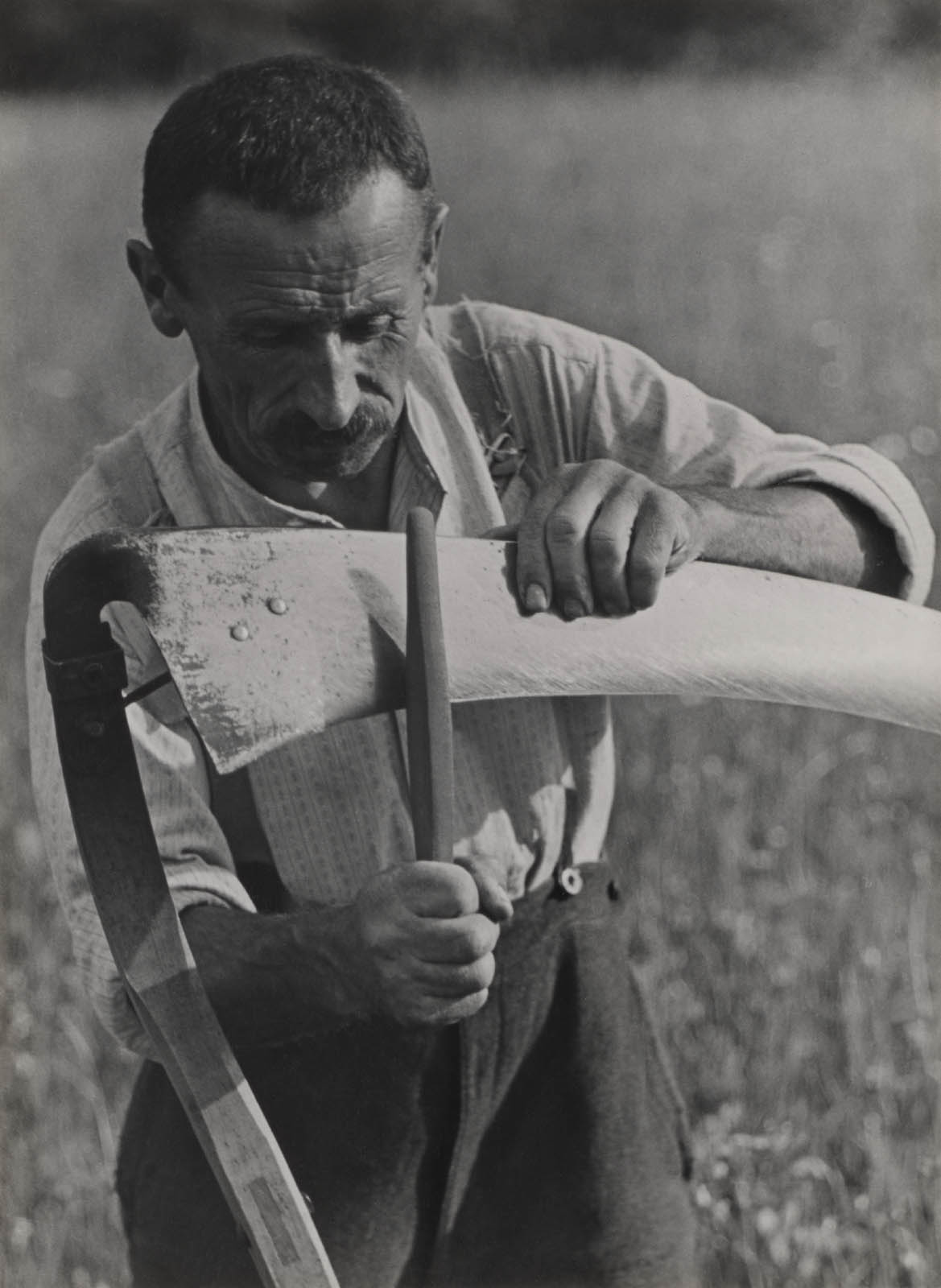

Newhaven Fisherman

1843-1845

20.1 x 14.7cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

James or “Sandy” Linton

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Newhaven Fisherman (detail)

1843-1845

20.1 x 14.7cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Jeanie Wilson & Annie Linton, Newhaven

1843-1845

19.2 x 14.7cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Jeanie Wilson & Annie Linton, Newhaven (detail)

1843-1845

19.2 x 14.7cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

David Octavius Hill (1802–1870) and Robert Adamson (1821-1848)

Malcolm Daniel

In the mid-1840s, the Scottish painter-photographer team of Hill and Adamson produced the first substantial body of self-consciously artistic work using the newly invented medium of photography. William Henry Fox Talbot’s patent restrictions on his “calotype” or “Talbotype” process did not apply in Scotland, and, in fact, Talbot encouraged its use there. Among the fellow scientists with whom he corresponded and to whom he sent examples of the new art, was the physicist Sir David Brewster, principal of the United Colleges of Saint Salvator and Saint Leonard at Saint Andrews University, just north of Edinburgh. By 1841, Brewster and his colleague John Adamson, curator of the College Museum and professor of chemistry, were experimenting with the calotype process, and the following year they instructed Adamson’s younger brother Robert in the techniques of paper photography. By May 1843, Robert Adamson, then just twenty-one years old, was prepared to move to Edinburgh and set up shop as the city’s first professional calotypist.

As important as Brewster’s introduction of Adamson to the calotype was, another introduction proved even more consequential. Just weeks after Adamson had established himself in Edinburgh, Brewster saw an opportunity to send business his way. On May 18, 1843, the Church of Scotland met in General Assembly amid great dispute over the role of the crown and landowners in appointing ministers. As the Assembly opened, the moderator, Rev. Dr. David Welsh, read an Act of Protest and led 155 ministers – more than one-third of those present – from the Assembly and through the streets of Edinburgh to Tanfield Hall, where in the days that followed they signed a Deed of Demission, resigning their positions and livelihoods, and established the Free Church of Scotland. Their act of conscience, at great personal risk and sacrifice, seemed heroic to many who were present, including Sir David Brewster and David Octavius Hill.

Hill was a locally prominent and well-connected painter of romantic landscapes and secretary of the Royal Scottish Academy of Fine Arts in Edinburgh. With the encouragement of the new Free Church, he resolved to paint a large historical painting of the signing of the Deed of Demission and, as was often the case for works of this nature, proposed to finance his painting through the sale of reproductive engravings of the finished work. In his advertisement for the engravings, issued within a week of the Disruption (as the upheaval was called), Hill wrote, “The Picture, the execution of which, it is expected will occupy the greater portion of two or three years, is intended to supply an authentic commemoration of this great event in the history of the Church … will contain Portraits, from actual sittings, in as far as these can be obtained, of the most venerable fathers, and others of the more eminent and distinguished ministers and elders.”

Brewster, sensing that Hill’s intention to sketch each of the several hundred ministers before they returned to the far corners of Scotland would be close to impossible, suggested that the painter use the services of the newly established Adamson to make photographic sketches instead. “I got hold of the artist,” Brewster wrote to Talbot in early June, “showed him the Calotype, & the eminent advantage he might derive from it in getting likenesses of all the principal characters before they were dispersed to their respective homes. He was at first incredulous, but went to Mr. Adamson, and arranged with him preliminaries for getting all the necessary portraits.” Within weeks Hill was completely won over, and the two were working seamlessly in partnership. As artistic director, Hill composed each picture, placing his sitters as they might appear in the finished painting.

Adamson operated the camera and carried out the chemical manipulations. Hill and Adamson were a perfect team. Hill, twenty years older than Adamson, was trained as a painter and had important connections in artistic and social circles in Edinburgh; he easily attracted a distinguished clientele to the team’s portrait studio at Adamson’s home, Rock House. Most of all, he possessed a geniality, a “suavity of manner and absence of all affectation,” that immediately set people at ease and permitted him to pose his sitters without losing their natural sense of posture and expression. Adamson was young but had learned his lessons well. He was a consummate technician, excelling in – and even improving upon – the various optical and chemical procedures developed by Talbot. Both men had a profound understanding of the way the world would translate into monochrome pictures.

If in May Hill had been incredulous, by June he was convinced; by July he was proud to exhibit the first photographs as “preliminary studies and sketches” for his picture, and by the end of the year he and his partner had photographed nearly all the figures who would have a place in his grand painting. Their hundreds of preparatory “sketches” ranged from single portraits to groups of as many as twenty-five ministers posed as Hill envisioned them in his ambitious composition. Some portraits, such as that of Thomas Chalmers, first moderator of the Free Church, were used as direct models for the finished work. However, at each sitting, Hill and Adamson made numerous photographs in various poses, and many photographs of the ministers have no direct correspondence with the painting. Still other portraits, of people who were not present for the signing of the Deed of Demission – but whom Hill apparently thought should have been – were used as models for the painting.

“The pictures produced are as Rembrandt’s but improved,” wrote the watercolorist John Harden on first seeing Hill and Adamson’s calotypes in November 1843, “so like his style & the oldest & finest masters that doubtless a great progress in Portrait painting & effect must be the consequence.” In actuality, though, it was so easy to make the portrait “sketches” by means of photography that Hill’s painting was ultimately overburdened by a surfeit of recognisable faces: 450 names appear on his key to the painting. The final composition – not completed for two decades and as dull a work as one can imagine – lacks not only the fiery dynamism of Hill’s first sketches of the event but also the immediacy and graphic power of the photographs that were meant to serve it.

By August 1844, Hill and Adamson clearly understood the value of their calotypes as works of art in their own right and decided to expand their collaboration far beyond the original mission, announcing a forthcoming series of volumes illustrated with photographs of subjects other than the ministers of the Free Church: The Fishermen and Women of the Firth of Forth; Highland Character and Costume; Architectural Structures of Edinburgh; Architectural Structures of Glasgow, &c.; Old Castles, Abbeys, &c. in Scotland; and Portraits of Distinguished Scotchmen. Although these titles were never issued as published volumes, photographs intended for each survive, and those made in the small fishing town of Newhaven are a particularly noteworthy group.

In a time as pervaded as ours is by photographic imagery, it is difficult to conceive that within the first few weeks of their collaboration, Hill and Adamson made more photographs than the two together had ever seen. In four-and-a-half years and nearly 3,000 images, they pioneered the aesthetic terrain of photography and created a body of work that still ranks among the highest achievements of photographic portraiture. Their collaboration ended not because of any artistic falling out between the partners but rather because Adamson, sickly from childhood, fell ill in late 1847 and returned to Saint Andrews to be cared for by his family. He died in January 1848.

Daniel, Malcolm. “David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (1821-1848).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hlad/hd_hlad.htm (October 2004)

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Newhaven

1843-1845

15.6 x 11.5cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

David Young (left); unidentified man

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Newhaven (detail)

1843-1845

15.6 x 11.5cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Jeanie Wilson, Newhaven

1843-1845

20.2 x 14.5cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Newhaven

1843-1845

19.9 x 14.5cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Unidentified boy; has also been called “King Fisher” or “His Faither’s Breeks”

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

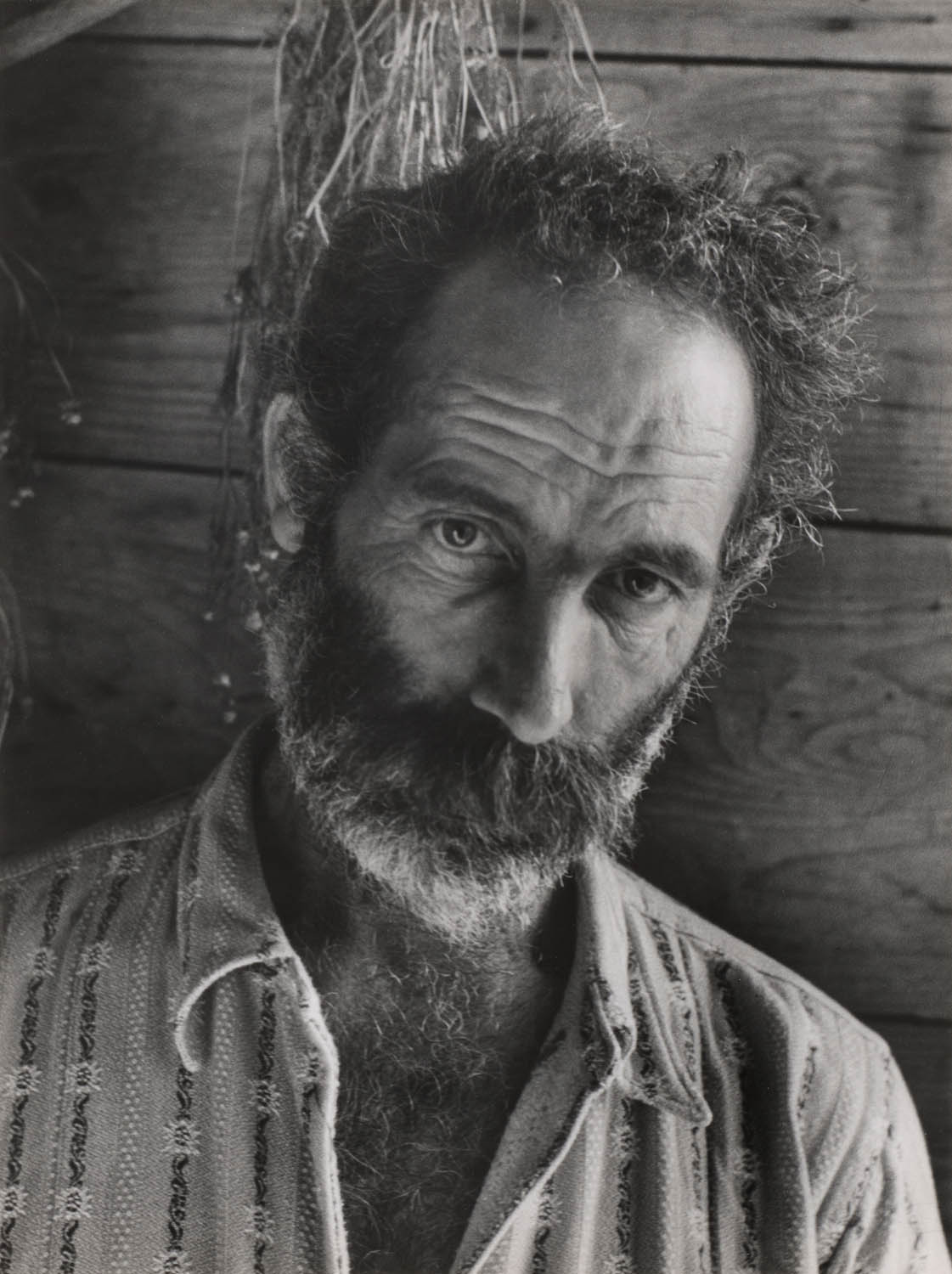

Newhaven Fisherman

1843-1845

20.6 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Willie Liston

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Newhaven Fisherman (detail)

1843-1845

20.6 x 14.4cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

A Newhaven Pilot

1843-1845

20.3 x 14.6cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

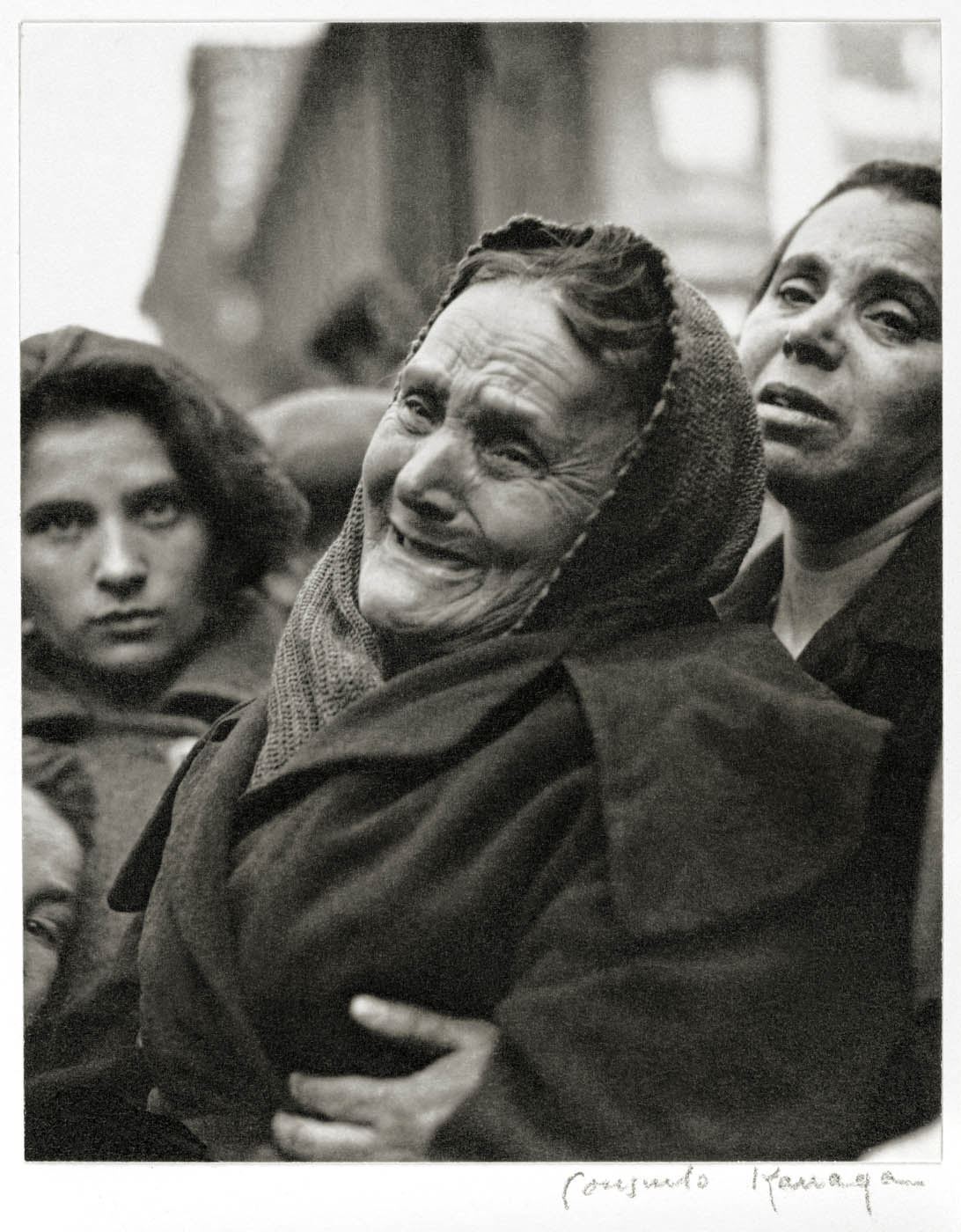

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Newhaven

1843-1845

14.7 x 20.1cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Group of unidentified women

Hill & Adamson (Scottish, active 1843-1847)

Robert Adamson (Scottish, 1821-1848)

David Octavius Hill (Scottish, 1802-1870)

Newhaven (detail)

1843-1845

14.7 x 20.1cm

Hill & Adamson Photography Collection

Gernsheim Collection

Harry Ransom Center, The University of Texas at Austin

Public domain

Harry Ransom Center

300 West 21st Street

Austin, Texas 78712

Opening hours:

Tuesday – Friday 10am – 5pm

Saturday – Sunday Noon – 5pm

Closed Mondays

![Leni Riefenstahl 'Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937) Leni Riefenstahl 'Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/leni-riefenstahl-schonheit-im-olympischen-kampf.jpg)

!['Leni Riefenstahl Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937) pp. 220-221 'Leni Riefenstahl Schönheit im olympischen Kampf' [Beauty in the Olympic Games] Berlin: Im Deutschen Verlag, (1937) pp. 220-221](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/leni-riefenstahl-schonheit-im-olympischen-kampf-a.jpg)

![Unidentified photographer. 'Untitled [Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York]' c. 1939 Unidentified photographer. 'Untitled [Weegee covering the morning line-up at police headquarters, New York]' c. 1939](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-a.jpg)

![Installation view of the exhibition 'Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle' at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at second left, Weegee's 'Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver)' (1939); and at top right, a magazine print of his photograph 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' (1941) Installation view of the exhibition 'Weegee, Autopsy of the Spectacle' at the Foundation Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paris showing at second left, Weegee's 'Man Arrested for Cross-Dressing, New York (Gay Deceiver)' (1939); and at top right, a magazine print of his photograph 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' (1941)](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/weegee-installation-hcb.jpg?w=650&h=650)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' 1941 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Young man smoking cigarette in crashed car while waiting for ambulance, New York]' 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-untitled-young-man-smoking-cigarette-in-crashed-car-while-waiting-for-ambulance-new-york-1941.jpg)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Tenement sleeping during heat spell, Lower East Side, New York]' May 23, 1941 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Tenement sleeping during heat spell, Lower East Side, New York]' May 23, 1941](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-tenement-sleeping-during-heat-spell-lower-east-side-new-york.jpg)

![Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947 Weegee (American, 1899-1968) 'Untitled [Fire in loft building, New York]' 1947](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/weegee-fire-in-loft-building.jpg)

![Weegee (American, born Ukraine (Austria), Złoczów (Zolochiv) 1899 - 1968 New York) '[Outline of a Murder Victim]' 1942](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/weegee-outline-web.jpg?w=840)

![Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape Near Taos, New Mexico)' Nd Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape Near Taos, New Mexico)' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kanaga-landscape-untitled-near-taos-new-mexico.jpg?w=840&h=506)

![Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape with Farmhouse)' Nd Consuelo Kanaga (American, 1894-1978) '[Untitled] (Landscape with Farmhouse)' Nd](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/kanaga-untitled-landscape-with-farmhouse.jpg?w=840&h=655)

![Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Bound Foot Exposed' [A Chinese Golden Lily Foot] 1870s Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Bound Foot Exposed' [A Chinese Golden Lily Foot] 1870s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/bound-foot-exposed.jpg)

![Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Caregiver' Caregiver [Woman carrying child] 1870s Lai Fong (Chinese, c. 1839-1890), Afong Studios. 'Caregiver' Caregiver [Woman carrying child] 1870s](https://artblart.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/lai-fong-caregiver.jpg)

You must be logged in to post a comment.